The Commodification of Suffering: The Purpose of a System is What It Does

In which I crash out over suffering, spectatorship, spectacle, Capitalist Horror, TikTok war crimes and having to write this essay.

“I hope for everyone reading this that one day you can be really and truly moved, even by a nightmare.” — “Bava As Much As Bataille,” Suburban Gothic

yes, I’m using my own quote as an epigraph. this is my newsletter, I’ll do whatever I want. bitch.

1

The first time I realized I was watching something that could hurt me was Alexandre Aja’s 2007 remake of The Hills Have Eyes.

As I recalled in a previous essay about early-2000s horror: “Watching Hills was the first time I was ever, in the most literal sense of the word, moved by a piece of media. I physically recoiled in my seat and cast my panicked gaze around at the other faces in the theater that night, searching for some confirmation that my visceral reaction was correct. I had entered Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.”

And years later, I’m still searching for ways to get back in.

2

I began this essay because I was frustrated with contemporary horror films. I wanted to feel challenged by the genre again, as I’d been in that theater when I was 13. I was going to write an elegy for confrontational horror. I was going to talk about Artaud and Bertolt Brecht and Torture Porn. And ask questions like, Should horror be cruel? Should it punish us? Can horror push us toward action — or is it all pacifying catharsis? This was meant to be an essay about the uses of violence and suffering in art. Instead, I lost my fucking mind.

3

To understand where it all went wrong, you need to know how Pascal Laugier’s 2008 film Martyrs has become the cipher through which I view the world for the past few weeks.

If you want to be punished, Martyrs is your confrontational horror film par excellence. It seeks to construct the hagiography of a woman named Anna as she’s drawn into the crosshairs of a pain-worshipping secret society. She’s tortured, flayed alive and, eventually, martyred in an endless series of experiments conducted to prove the existence of an afterlife.

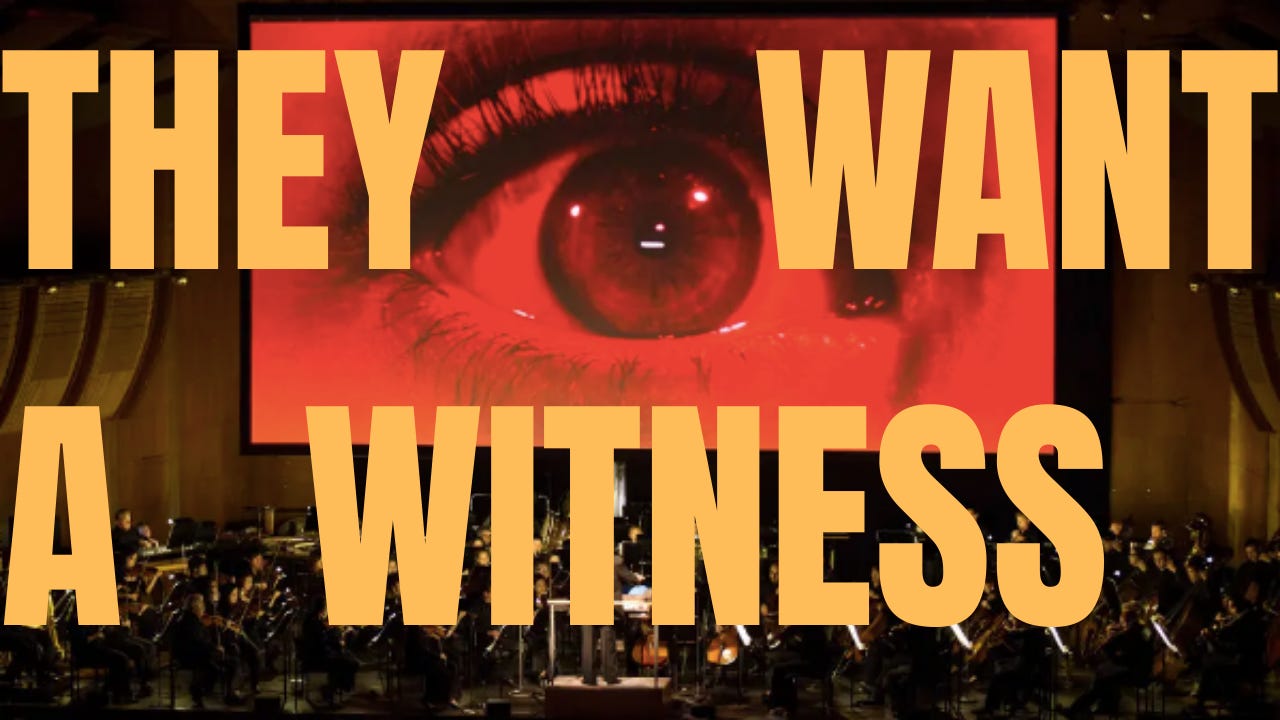

You need to know that the act of seeing is vital to the film’s ethos, made all the more clear by its post-script, which defines the word martyr as, simply, a witness. There’s no blind faith here. The secret society believes that by bringing Anna to the brink of death, she’ll be able to see into the afterlife and relay what waits beyond before she dies.

However — and this is key — first, she must suffer. If she’s able to transcend her suffering, she becomes a martyr; if she succumbs to it, she’s merely a victim. The suffering is important. First — the cult believes — you suffer; then you see.

4

The cult’s leader, Mademoiselle, explains to Anna, “People no longer contemplate suffering, young lady. That’s how the world is. There are only victims left. Martyrs are very rare. A martyr is something else. Martyrs are extraordinary beings. They survive pain. They survive total deprivation. They bear all the sins of the earth. They give themselves up. They transcend themselves. Do you understand that word? They are transfigured.”

While not ostensibly a religious sect, the society that drives the plot of Martyrs draws a clear parallel to Christianity (Laugier is a lapsed Catholic). The film asks us, Is there grace in suffering? Well, the Christians would certainly say yes.

“This is one of Christianity’s most gripping promises: that violence need not remain simply violence; it can be changed, via faith, into suffering, which, due to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, is never in vain,” Maggie Nelson writes in her “reckoning” with depictions of extreme violence in media, The Art of Cruelty.

The Crucifixion lies at the heart of Christianity’s victim complex. Christ’s martyrdom made attacks on both insiders and outsiders a rite as well as a moral necessity. And in a religion where violence “is never in vain,” it can be both accepted and doled out at once, creating a never-ending cycle of suffering.

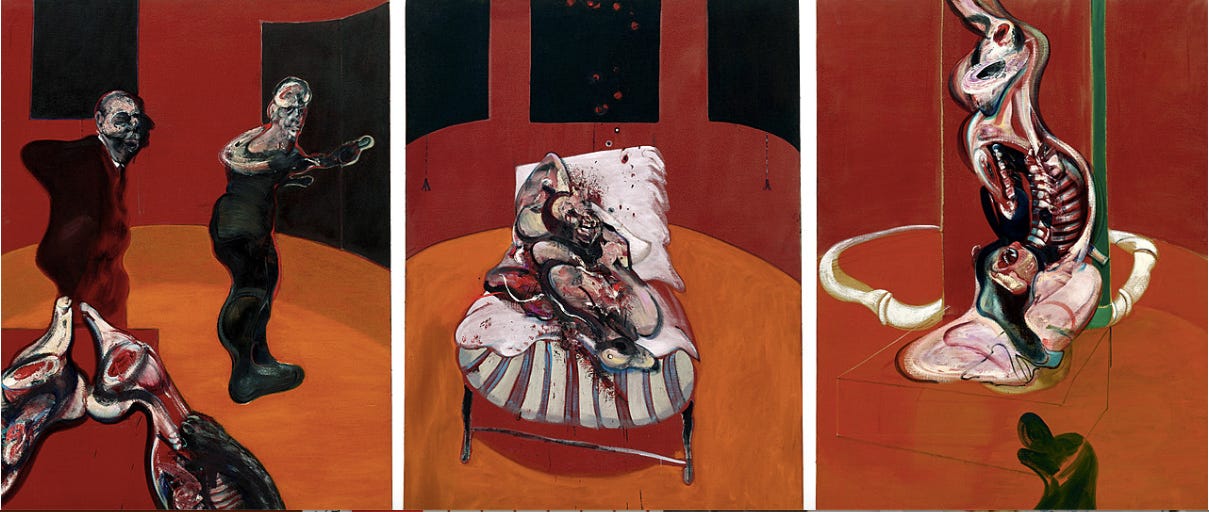

In discussing the violent depictions of crucifixion in Francis Bacon’s paintings, Nelson explains, “In short, if you remove the story of the Passion, if you remove the radiant, suffering face and body of Jesus, if you remove the specter of a miraculous Resurrection, you are left with an act of bald cruelty — a situation of meat — and some aggregate of its victims, perpetrators, witnesses, and accomplices.”

5

Martyrs and religiosity and Jesus — and, wait, didn’t David Edelstein mention The Passion of the Christ in his essay where he coined the term Toture Porn? See, the films mirror our current abjection back to us and they can either reaffirm that reality or disrupt it. We watch these films but in Martyrs, watching, seeing, witnessing, is a false god. It’s only through experience that we can really know, you know? But it all make sense really because it’s all about experience versus seeing — or experience as seeing. Linda Williams’ body genres. Active versus passive. Watching versus doing. Violence as art. Violence as entertainment. Dialectics and ego death and the path to the divine. Witnessing — suffering — grace — don’t look away — do you get it? Do you see? Right? Right. You get it.

6

So… this is where I began to lose it a bit.

7

And in the midst of all of this, I hate Schindler’s List!

Don’t get me wrong, Steven Spielberg’s overwrought melodrama is a fine enough film, but I think it utterly fails as a Holocaust film. Mostly due to an overreliance on kitsch and sentimentality — among other criticisms. In an effort to teach American audiences about the horrors of the Holocaust, Spielberg positions it as a unique event separate from any historical context that came before or after, placing it in a far-off past (or another universe entirely where everything’s in black-and-white and Germans exclusively speak English). Ending in a sunny present day (you know this because it’s in color — we’ve finally made it the bright, beautiful ‘90s), audiences are free to leave the film perfectly complacent in the knowledge that everything they’ve witnessed for the past three hours has been neatly tied up and packed away, no need to think about it ever again.

The one thing Schindler’s List gets right is the never-ending bureaucracy of fascism, making it bedfellows with the Marquis de Sade’s infamously cruel 120 Days of Sodom. It is — at its heart — not a war film, but a workplace drama. However, unlike Sade, whose cruelty becomes tediously boring, the evil in Schindler’s List is anything but banal.

The paperwork scenes, of which there are many, are absolutely thrilling. The film suggests that the way to combat fascism is to simply do bureaucracy better than the fascists. The Nazi’s are making lists of Jews? Then, we’ll make better, more moral lists! At no point does anyone in the film question the existence of the lists in the first place.

Ultimately, it fails in this sense, as well. As we watch Oskar Schindler buy and sell human beings under the guise of their status as “essential workers” or art-of-the-deal his way through the Third Reich, we’re not meant to ask questions like: “Why is someone’s life tied to their ability to work?” “What if the only thing standing between you and fascism was your boss?” “Why is money the ultimate hero of this story?” We’re only meant to think: Wow, Oskar Schindler is so cool.

The film tells us that Schindler can only save the “Schindlerjuden” (my god, that phrase.) by capitulating to the terms of power so well that he does them better than the other Nazis. This, the film suggests, is the Nazis real failing: that they cared more about genocide than money.

Look to Schindler’s final lines in the film to understand its true moral: “This pin. Two people. This is gold. Two more people. He would have given me two for it, at least one. One more person. A person, Stern. For this.”

But, understand, the tragedy he’s lamenting here isn’t that we’re trading people for gold — but that he didn’t have more gold to trade. Schindler’s List doesn’t want to destroy the society that made the Holocaust possible — it wants its victims to conform to it better.

8

Martyrs portrays a similar assembly line of suffering as Schindler’s List. Here, the bourgeois perpetrators carry out their torture in a nice French suburb as if they’re clocking in for a 9-to-5 job — careless yet dutiful.

In an essay on the film, Gwendolyn Audrey Foster takes note of this systematized violence, even likening it to the Nazis. “But most importantly, I think, Martyrs strongly suggests, largely through the use of the mundane, that routine torture goes on every day in most homes and families and in the institutions that hold up capital: patriarchy, the church, law, the military, and society. Laugier is careful to render ritualized abuse as mundane almost to the point of boredom. The torturers look as bored as McDonald’s workers or stockbrokers.”

Leaving behind Spielberg’s melodrama, the violence in Martyrs is brutal and matter-of-fact (“a situation of meat,” as Nelson put it). It’s not, however, the point. It’s simply a means to an end.

We might consider these films as part of a subgenre we’ll call “Capitalist Horror” — stories that reflect a system that justifies any means for its ends, that prioritizes productivity over humanity, that builds violence and dehumanization into its workflow.

Martyrs ends with a similar capitulation to power as Schindler’s List, wherein Anna only finds peace in giving in to the violence she’s experiencing, fully submitting to the terms of the powerful people exploiting her. It’s saved, however, by its nihilism. Where Schindler’s List ends on a kitschy, feel-good high, Laugier leaves us with the sick feeling that violence only begets more violence and everyone — as we’re all implicated — suffers under this way of life.

9

In another similarity between the two, Schindler’s List is a hagiography of sorts itself.

10

Or as Jewish-American writer Corey Robin wrote in 2016: “By blackmailing ourselves into thinking that we must put ourselves through a taste of Auschwitz, we are imitating unconsciously the Christian mystics who tried to experience in their own flesh the torments of Christ on the cross. … In certain ways, the Jewish American sacramentalizing of the Holocaust seems an unconscious borrowing of Christian theology. That one tragic event should be viewed as standing outside, above history, and its uniqueness defended and proclaimed, seems very much like the Passion of Christ.”

11

I’m also interested in the act of seeing. Specifically, how it intersects — or doesn’t — with action.

In “The Emancipated Spectator,” Jacques Rancière lays out the problem like so: “But spectatorship is a bad thing. Being a spectator means looking at a spectacle. And looking is a bad thing, for two reasons. First, looking is deemed the opposite of knowing. … Second, looking is deemed the opposite of acting. He who looks at the spectacle remains motionless in his seat, lacking any power of intervention. Being a spectator means being passive. The spectator is separated from the capacity of knowing just as he is separated from the possibility of acting.”

When we watch Martyrs, we, the audience, are also witnesses, after all. Foster observes, “We become martyrs in a sense. This small gesture shocks us to our core by reminding us that even while we are safely watching a fictional story, real events of incredibly painful torture, ritual abuse, and sanctioned murder surround us and we are responsible, precisely because we do nothing about it.”

In interviews, Laugier has repeatedly said Martyrs came from a “pessimistic” time in his life, one in which he was experiencing a great deal of pain and the film acted as a way for him to communicate that pain to the world by forcing it on us.

I respect this as an artistic ambition. To have a feeling so strong you have no choice but to smear it on the world. Laugier is afflicting us with his pain not as a punishment but as an act of community. It feels more pure than the cheap thrills of American-made Torture Porn films like Hostel and Saw.

But does it create the flow of empathy Laugier and Foster posit it does? Can art make us kinder? Does it ever spur action?

In The Art of Cruelty, Nelson ultimately concludes, “probably not.”

“The most interesting of this work—past, present, or future—is or will be that which dismantles, boycotts, ignores, destroys, takes liberties with, or at least pokes fun at the avant-garde’s long commitment to the idea that the shocks produced by cruelty and violence—be it in art or political action—might deliver us, through some never proven miracle, to a more sensitive, perceptive, insightful, enlivened, collaborative, and just way of inhabiting the earth, and of relating to our fellow human beings.”

And yet! Plenty of spectators — like Foster with Martyrs — are still challenged by the shocks produced by cruelty in art. And yet we still demand the viewership of violence.

12

But I understand Nelson’s warning against conflating representation with experience — or as Namwali Serpell puts it in “The Banality of Empathy,” “[Art] simulates empathy, so we believe it stimulates it.”

13

It’s not so much that I disagree with Nelson’s assessment. There is a difference between art and experience. Rather, I wonder why, in light of this agreement, I still think words, art, images, and so on might, in her words, “deliver us … to a more … just way of inhabiting the earth, and of relating to our fellow human beings,” if even indirectly.

After all, there’s evidence it works in the opposite direction. At one point in The Art of Cruelty, Nelson draws on an anecdote in which officials from the U.S. military and the FBI met with the showrunners of the cable TV series 24 in an attempt to convince them to walk back the show’s portrayals of American intelligence agents’ use of extreme torture methods. Apparently, due to the show’s influence, real American soldiers were “decreasingly inclined to take seriously the importance of adhering to international military law.”

So, depictions of violence can affect our relationship to real violence.

In my 2000s horror essay, I made a similar observation to Foster in her piece about Martyrs: “It’s cinema that implicates us — you — and I can’t help but feel that’s why people are so quick to denounce it. If you recoil, as you should, who are you recoiling from? If you’re disgusted, as you should be, why does it linger long after the credits roll?”

14

Then again, is this the same sacramentalizing Robin critiqued? Does it all just lead to the same victim complex at the heart of Christian persecution? At what point does simulated suffering translate to real-world retribution?

15

As Robin pointed out in a different piece in 2015: “It’s long been remarked that the Holocaust and Israel have replaced God and halakha as the touchstones of Jewish experience and identity. The Holocaust is our deity, Israel our daily practice.”

16

Oh no, here she goes.

17

Well, yes! Did you think I was going to write a screed about depictions of violence, spectatorship and political action and not bring it up? Are you new here?

18

When TikTok was almost, but not really, banned in the U.S., many theorized online that one of the leading motivations behind the ban was how many people were using the app to spread information about the genocide in Gaza. Not no — but how then do we reckon with the fact that the same app is also being used by IDF soldiers to document the genocide they’re committing?

Do I believe officials in the American and Israeli governments were surprised by how many Americans identified more with the Palestinians than the bombs falling on them? Sure. But does that equate to them caring enough to change their actions?

Put another way: Do we believe they believe an image exists that will move us so profoundly that we’ll intervene in a substantial way?

19

When a different American war crime was exposed after images of U.S. Army and CIA members torturing people in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were published, the images themselves quickly became the story.

The cheerful smiles of the Americans as they posed with degraded, dehumanized or dead human beings prompted questions from the public about what might lead someone to engage in such sadistic behavior, why they would photograph it, or, as Rush Limbaugh wondered, “I’m talking about people having a good time, these people, you ever heard of emotional release?”

The actual policy that facilitated the acts in the photos got lost in the chatter. Or worse.

In Nelson’s estimation, the Abu Ghraib images work in tandem with fictional depictions like 24 and the Torture Porn films of the era not to disturb or shock, but rather normalize torture for the American public.

Referencing Susan Sontag’s assertion that images hold equal potential for shock and cliché, Nelson writes, “… [That] partially explains how the iconic image of the hooded pisoner at Abu Ghraib forced to hold a foreboding wire in each hand could literally sicken one’s stomach when first viewed, then move on to become a much-parodied image (e.g., on the satirical posters that appeared throughout the New York subways not long after the Abu Ghraib story broke, posters that borrowed the dinstinctive design of Apple’s iPod campaign, but substituted the word “iRaq” for “iPod,” and featured the silhouette of the hooded man lieu of the iPod’s silhouetted dancer).”

And now it all circles back to the attention economy and the primacy of the Image. This is the dream of a neoliberal attention economy: If you post enough, real change will follow.

When does documenting something become more important than what’s being documented? In Martyrs, the cult places more value on what a martyr might see than on her life. At what point does all this image-making become a spectacle that only benefits the system?

20

After all, we’re a little past the point of the apathetic cruelty of Capitalist Horror films, past violence as nothing more than policy. When the White House is gleefully posting videos of mass deportations on TikTok and noted dog killer Kristi Noem is posing for photo ops at Salvadoran prisons, this time in front of the human victims of her cruelty. ICE is filming and broadcasting its raids. Like the IDF’s TikToks, these images aren’t leaked glimpses behind closed doors — they’re a message. The cruelty is the point.

21

As Nelson puts it, “[The logic that Americans only support capital punishment because of ignorance] relies on the hope that shame, guilt, and even simple embarrassment are still operative principles in American cultural and political life—and that such principles can fairly trump the forces of desensitization and self-justification. Such a presumption is sorely challenged by the seeming unembarrassability of the military, the government, corporate CEOs, and others repetitively caught in monstrous acts of irresponsibility and malfeasance... [They] are not ashamed, and they are not going to become so.”

22

And at this point, it’s worth mentioning that, no, we should not, as a practice, look the other way. Asking questions about how and why we consume suffering is not the same as advocating for political apathy. It shouldn’t have to be said. But this is the illiberal internet, so I’ll say it.

But that’s why people hate contemporary leftists, right? Because we sit around philosophizing about suffering more than actually doing anything to change the conditions under which it thrives? What’s even the point of writing any of this — of thinking about these things at all — if it won’t help anyone? I mean — I — Well —

23

I resisted working on this essay every step of the way. I didn’t want to contemplate suffering. I didn’t want to rewatch Martyrs. I didn’t want to rewatch Schindler’s List. I didn’t want to watch a video of a Massachusetts college student being robbed, abducted and human trafficked by federal agents five times a day for the past week. I didn’t want to lose my mind. But even if I felt the reflex to look away, at this point, where else is there to turn?

24

In “The Banality of Empathy,” Serpell draws on Paul Bloom’s distinction between “cognitive empathy” and “emotional empathy.”

“With a simple thought experiment—you pass by a lake where a child is drowning—Bloom shows that emotional empathy is often beside the point for moral action. You don’t have to feel the suffocation, the clutch of a throat gasping for air, to save someone.”

Or per The Art of Cruelty, “‘You do not necessarily feel [compassion],’ Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa once warned a student who was worrying about how to act compassionately without feeling it first, ‘You are it.’”

25

To answer my previous question, people are intervening in substantial ways. I’ve written before about the organized action against Atlanta’s Cop City. You can read about the motivations of two of the Merrimack Four activists who temporarily shut down a facility that supplies weapons to Israel in this interview with

. New webs of resistance are forming every day in response to Power’s mad scramble to snuff us out.And, I imagine, much of this action is rooted in cognitive empathy rather than emotional. The average American isn’t capable of attaining true emotional empathy from the images of destruction in Gaza, which they’re mainly experiencing through social media apps. We’re unable to fully understand what devastation like that feels like. But we don’t have to. We can do the moral thing anyway.

26

Here, I’ll trot out the Laugier quote everyone who’s ever written about Martyrs references.

“Our epoch is not very glorious. There are no utopias, ideologies have collapsed and our faith in the future with them.1 I realise it’s not very original to say this, but I really believe that the Western world is sick. Individual anxieties are at their highest, everyone lives in a constant low-level fear, it feels like we’re going to crash into a wall, there’s something very deathly in our current society. Horror cinema allowed me to express this in a very direct way. Martyrs is almost a work of prospective fiction that shows a dying world, almost like a pre-apocalypse. It’s a world where evil triumphed a long time ago, where consciences have died out under the reign of money and where people spend their time hurting one another.”

27

This echoes, albeit nihilistically, something one of the Merrimack Four, Paige Belanger, said in the Vanishing Points interview. “I feel like doing this was inevitable. I have always felt an acute sense that reality as we know it is not the one in which we are meant to be living. We are all so intensely alienated from nature, from our own humanity, from life itself. I’ve always imagined a world outside this inescapable alienation, although I wouldn’t always have framed it that way. The only time I’ve ever felt like I fit into this world is when I have been fighting to bring a new one into being.”

28

This imperative to imagine underscores the difference between spectatorship and action — and the uses of both. While witnessing may be subordinate to compassion (as an action) in political solidarity, it has a place in our ability to question the nature of our material conditions. We bear witness, then we ask questions about the world, about ourselves, about the way we’ve always believed things to be. This questioning is important.

All the while, art is opening us up to new possibilities that help us forge new ways of being. Possibly even a “more sensitive, perceptive, insightful, enlivened, collaborative, and just way of inhabiting the earth, and of relating to our fellow human beings” (Nelson).

29

Witnessing the ultra-violence of Martyrs (or The Hills Have Eyes or Funny Games or any other confrontational film) puts the viewer in a bind. You’re forced to watch something bad happening while being helpless to stop it. This is what makes it cruel — what it does to us when we’re at the mercy of the tyranny of the director.

Maybe it’s in this simulated helplessness where its true revolutionary potential lies. The feeling of powerlessness is a prevailing theme in today’s political discourse. Of course, the cinematic spectator is actually helpless to stop what they’re seeing — the political spectator is not.

30

In “The Emancipated Spectator,” Rancière concludes, “I’m aware that all this may sound like words, mere words. … Breaking away from the phantasms of the Word made flesh and the spectator turned active, knowing that words are only words and spectacles only spectacles, may help us better understand how words, stories, and performances can help us change something in the world we live in.”

31

If Martyrs is the key to understanding suffering and spectatorship — and if this essay is proof of anything, it’s that it most certainly is not; but whatever, we’re almost finished — then perhaps the answer’s in the ending. Anna remains Christ-like all the way to the end (even embracing her torturer at one point) not because of victimization or retribution — but love. It’s her love for her friend who dies at the beginning of the film that allows her to let go of herself and find peace in the face of inevitable death. This is her transcendence.

It was never about suffering. It was about compassion.

32

Pascal Laugier turned his pain into a piece of art that confronted me, challenged me, moved me. It engaged me in an endless dialectic about suffering and capitalism and modernity and pain and love, and while it didn’t bring me closer to understanding, I can accept the spectacle is only spectacle, and instead try to find the meaning out there, in the world, with you.

not in my world. not in the world I’m living in.